21 July -31 August 2006, Shanghai China

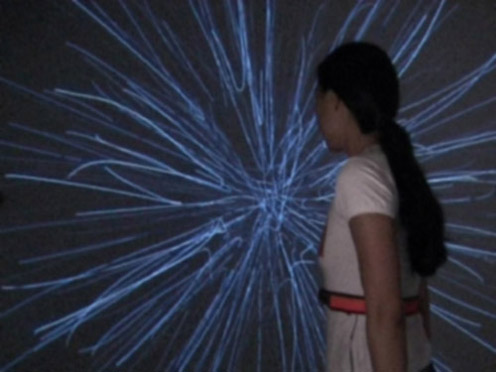

Drawing Breath v.2, George Khut and John Tonkin

The Strange Attractors: charm between art and science exhibition curated by Antoanetta Ivanova (Novamedia) and exhibited at the Zendai Museum of Modern Art in Shanghai provided a showcase for a diversity of Australian arts-science explorations, and a valuable opportunity for local Shanghai artists and scholars to immerse themselves in the possibilities and critical issues surrounding art-science collaborative research work more generally, with works by Drew Berry, Justine Cooper, Peter E Charuk, Jon McCormack, Jane Quon, SymbioticA, The Tissue Culture & Art Project, Julie Ryder, Hellen Sky, Mari Velonaki and myself (with John Tonkin).

A one-day art/science symposium was held in conjunction with the exhibition and featured presentations by exhibiting arts-science collaborators and a panel with local practitioners and academics including Wang Nanming, Hu Jieming, Ma Lin, Jin Jiangpo and Australian artists Lindsay Broughton and Oron Catts. This was also my first visit to China, the birthplace of my paternal grandfather, and in this respect represented a form of ancestral homecoming, complicated by the fact that most Chinese didn’t recognise me as Chinese in any way at all, given my mixed racial appearance and inability to speak Mandarin.

The exhibition highlight (in terms of interest from local media), was a collection of bio-tech works presented by SymbioticA including The Pig Wings Project, Disembodied Cuisine and MEART – The Semi-Living Artist. These provocative works generated much discussion amongst local artists and academics: during the exhibition symposium event, most of our discussions with local artists and academics seemed to centre around the question of ‘is this art’? Considering the sensational and provocative nature of some of the contemporary Chinse art we experience in the West, this may seem surprising. On reflection this ambivalence, highlighted significant differences regarding the status of the individual and speculative research practice in our two cultures.

Much contemporary Chinese art seems to be directed by a very real sense of urgency regarding the status of the individual in a rapidly changing social, cultural and economic landscape. By contrast, most of the works on exhibition at Strange Attractors addressed questions relating to the natural sciences: biology, taxonomy, ecology, artificial life simulations etc. The speculative nature of these practices shifts our attention away from a concern for the artist as hero/anti-hero and social commentator towards a fascination with the physical world and the politics of its manipulation by science, industry and technology. While it could be argued that such concerns are irrelevant to the recent history and aspirations of contemporary Chinese society, judging by some remarks from the Chinese symposium delegates, this may no longer be the case.

Towards the end of the final symposium session Jane Quon (another Australian of mixed Chinese and Anglo-Celtic ancestry) and I attempted to introduce the Pragmatist aesthetics of 1930’s philosopher John Dewey as a way of shifting discussion away from questions of classification towards an appreciation of art as an instrumental practice that can add meaning and value to our lives. Dewey’s experiential approach to art, as developed in ‘Art as Experience’ focuses on arts capacity to intensify life experiences in ways that add value, meaning and enjoyment to our lives, but without preparation, the translation of these ideas proved too difficult a bridge to cross in such a short time.

The work I presented at Strange Attractors was Drawing Breath: Three, an interactive work developed in collaboration with fellow artist and interaction-designer John Tonkin. Although earlier versions of this work had toured through South East Asia with the Gallery 4AAsialink produced exhibition Open Letter this was the first time that I was able to travel with the work to an Asian culture, and I was very interested to be able to observe first hand how people from another culture would negotiate such a work. Whilst not referencing notions of identity and ethnicity in any direct way, I have always felt these body-focused artworks to have been deeply influenced both by my early childhood experiences of Kung-Fu, Qi-Gong and more recent experiences with of Zen meditation and Western Somatic bodywork (Feldenkrais Method). Being on-site for a few days after the shows opening enabled me to observe how local audiences responded to the works. Visitors seemed to enjoy the experience for its formal simplicity and intense kinaesthetic effect: watching sinuous lines expand across the breadth of the gallery wall with each breath, and the peculiar sense of closeness one experiences when lines from one own breathing patterns intersect with anothers. Breathwork is a common technique used in many forms of Chinese martial arts, qigong and meditative practices, so the idea of breath as a basis for an aesthetic experience was not without precedence. Chinese audiences young and old seemed to connect to this aspect of the work in a way that clearly owed something to these shared cultural references, and these responses certainly helped bolster my then rather deflated sense of Chinese-ness.

Getting-down to the installation of Drawing Breath: Three, Zendai Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Helen Sky.

Strange Attractors launch event: curator Antoanetta Ivanova with local officials, Zendai corporation directors and media, photo by George Khut

See George’s Alembic and Retort work in Super Human: Revolution of the Species

Drawing Breath, 2004 (with John Tonkin) from George Khut on Vimeo.

Tags: aesthetic experience, art science collaborations, artificial life simulations, bio art